02 Aug The Tariff-Tax

“The only difference between death and taxes is that death doesn’t get worse with every Executive Order.” – The Lonely Realist (with thanks to Will Rogers)

Tariffs are taxes imposed on goods entering the country. They are a form of consumption tax because they add to the cost of imports and of goods manufactured in the U.S. using imported materials (whether or not the finished goods are consumed domestically or exported to other countries). Those additional costs are paid by the businesses that import the goods/materials –that is, tariffs are paid by American-based businesses and are not a cost to foreign countries or foreign countries’ exporters. If an American importer chooses to absorb those costs, the tariff-tax will reduce the importer’s profits, pressuring the importer to reduce its overhead (including employment) and capital investment, which will weigh on GDP (which grew at only 1.3% over the first 6 months of 2025). Today’s level of tariffs also will encourage other countries to impose costs on U.S. imports that will have a similar impact. However, if the American importer is unwilling to absorb the tariff costs, it can increase the price it charges its customers to fully or partially offset the tariff-tax. In that case, the higher price will be inflationary. Assuming that last week’s level of tariffs (@14%) will continue, the Congressional Budget Office has estimated that tariffs will increase U.S. inflation by 0.4%. They also will increase global inflation. Whatever the burdens, because of America’s Federal debt and deficits, America needs the additional revenue…, with tariffs set to generate additional Treasury inflows ($230 billion/yr. according to Yale’s Budget Lab).

To date, the Trump Tariffs have not measurably increased inflation, leading some to conclude that businesses have been absorbing and will continue to absorb the tariff costs. That’s premature. In addition, the Dollar, contrary to expectations, has weakened, making U.S. goods more competitive. If these trends continue, foreign manufacturers can be expected to shift production to the U.S., thereby furthering President Trump’s goal of onshoring manufacturing. However, many economists see different causes and widely differing outcomes. They believe that American businesses stockpiled goods and materials prior to Liberation Day (the apex of “tariff terror”), that they therefore will have no need for additional goods or materials for some months, that they then will have to raise prices to compensate for the added costs of acquiring tariffed goods and materials, and that they thereafter will be reluctant to incur the long-term capital costs required to domestically manufacture targeted tariffed goods (due in part to the risk of changing American policies). Those economists accordingly are forecasting increasing inflation and only limited capital investment in U.S. manufacturing. Moreover, because recently announced tariff-and-trade deals don’t target specific goods and do target widely-used materials, their forecast is that the Trump Tariffs will increase manufacturing costs. Further, since recent trade deals require trade partners to import energy and food from America, increased demand for energy and food will drive up domestic prices and accelerate an incipient inflationary trend.

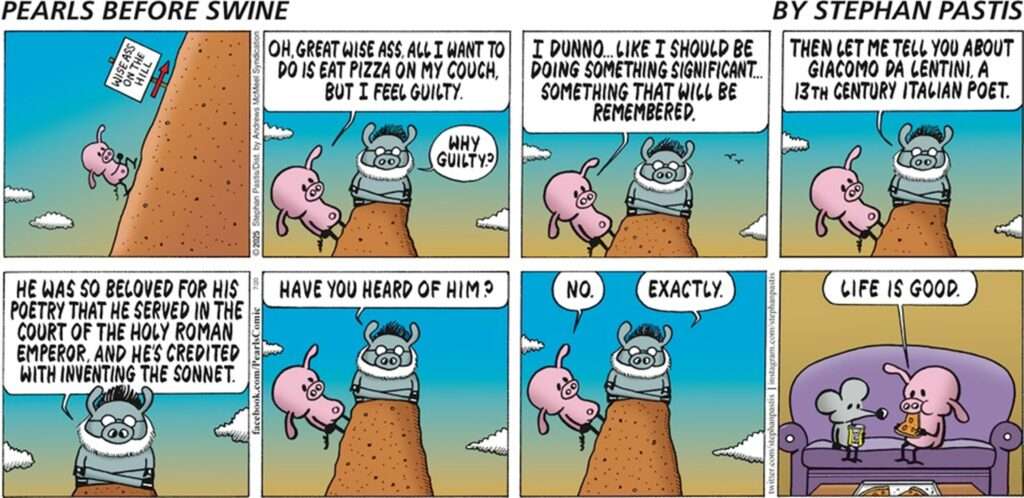

The reality is that no one knows what’s going to happen. There simply is too much uncertainty and too many variables exerting a push-pull on the economy and on decision-making.

As TLR has observed, a consumption tax, which the Trump Tariffs are, is superior to America’s burdensome and special-interest dominated Internal Revenue Code (comprising 6,800 pages of tiny text plus 75,000 pages of regulations). However, if the Trump Tariffs are intended as a substitute for America’s income tax, they raise inadequate revenue and increase compliance costs. Despite the need for taxes to fund annual Federal deficits of $2+ trillion, Trump tariff-taxes will barely dent the deficit and will leave untouched $37+ trillion of increasing national debt. Existing income tax collections (reduced by OBBB cuts and cuts to the IRS budget) combined with new tariff-taxes also will add complexity to an already super-complicated tax system. Moreover, the Trump Tariffs are not targeted at sector-specific products or materials designed to reduce consumption inefficiencies and incentivize onshore manufacturing. For example, the biggest gainers from the tariffs imposed on Japanese and EU imports will be Japanese and EU automakers, a perverse outcome since Japanese and EU tariffs @15% are intended to protect U.S. manufacturers from their Japanese and European competitors. Instead, American automakers will be tariff-taxed at a higher rate on imports from Canada and Mexico (where tariffs are set at 35%, although certain auto components are temporarily excluded) and on steel (where tariffs are set at 50%).

TLR has long-advocated tax simplification through adoption of a consumption tax, namely the comprehensive Competitive Tax Plan, that would complement and largely substitute for income taxation. TLR believes that a consumption tax is an optimal means for reducing America’s deficits and debt (especially if coupled with reduced Federal spending) and would eliminate most of the Internal Revenue Code’s inefficiencies and giveaways. To be enacted, the Competitive Tax Plan would have to be thoughtfully crafted by the House Ways and Means Committee, passed by both the House and Senate, and signed by the President pursuant to the process set out in America’s Constitution. That contrasts with the Trump Tariffs, which have been and are being imposed via Executive Order (which, because they have questionable Constitutional validity, may be required by the courts to originate in and be enacted by Congress). Mis-advertised as falling on foreigners rather than American businesses, the burdens and randomness of the Trump Tariffs are furthering uncertainties, freezing business planning, and compounding instabilities that have the potential to unsettle both America’s and the world’s economies.

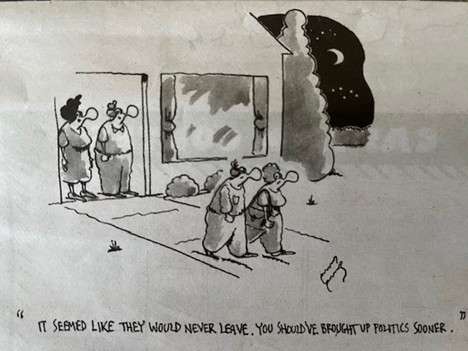

A number of today’s pundits are predicting that the Trump Tariffs will result in increased (though perhaps transitory) inflation, followed by declining profits and GDP. Others are confident that current uncertainties have transactional benefits and will be resolved favorably for America. Most express certainty about their forecasts. That’s because there is more than enough data to support whatever conclusion is desired, resulting in confirmation bias that corroborates each person’s predetermined belief system. “Non-pundit” economists, however, are expressing concerns about multiplying risks. Despite President Trump’s call for lower interest rates, current U.S. rates may be the safer course to ensure long-term economic health.[1] If the Federal Reserve nevertheless executes on the President’s demands requests for easing interest rates before the effects of tariffs become clearer, there is a risk of escalating rates down the road. In addition, should tariff instability continue, or should foreign governments retaliate, the world could spiral into trade warfare. The wisest prudent approach, therefore, for those without a predetermined belief system and with an aversion to risk, is to pursue investment convexity. A study of history reveals that there have been many periods of high tariff-taxes…, and that none ended well. Be careful out there!

_____________________

[1] Per John Authors: “Overnight rates in the US are the highest among developed countries because a) the US economy is in better shape than the rest of the world, and b) it’s where new tariffs will be paid, and not anywhere else. At the margin, the emerging new global trade order will be inflationary for Americans and deflationary for everyone else. Of course US rates are higher.”

Finally (from a good friend)

No Comments