15 Mar Presidential Immunity

“Did the Supreme Court’s 2024 decision in Trump v. U.S. provide a ‘legal pass’ for Presidential criminal acts?” – The Lonely Realist

No.

There has been much hand-wringing over the Supreme Court’s July 1, 2024 decision in Trump v. U.S. holding that “Under our constitutional structure of separated powers, the nature of Presidential power entitles a former President to absolute immunity from criminal prosecution for actions within his conclusive and preclusive constitutional authority. And he is entitled to at least presumptive immunity from prosecution for all his official acts.” This does NOT mean that Presidents, including President Trump, have received a “legal pass” for their criminal actions. A legal parsing of the decision reveals that the Court provided appropriate guidelines for lower courts to use in making such determinations.

Article II, Section 1, of America’s Constitution vests “conclusive and preclusive” executive power in the President. Article II therefore guarantees the authority of Presidents to make unfettered “executive decisions” – unfettered meaning without fear of criminal prosecution. What, then, constitutes an executive decision? The Court divided that question into two parts: What constitutes “an exclusive exercise”? And what precisely is “executive power”? Although the Court confirmed that a President’s “official actions” as America’s chief executive are protected by the Constitution – and that actions that are not “official” are not protected –, which actions does the Constitution delegate, and delegate only, to the President? President Trump had argued that because a President is “absolutely immune” from civil damage liability, he also must be “absolutely immune” from criminal prosecution. The Court rejected that argument. Had the Court accepted it, that indeed would have given Presidents a “blank check.”

In drawing necessary Constitutional lines, the Court determined that the “[c]ritical threshold issues are how to differentiate between a President’s official and unofficial actions, and how to do so with respect to the indictment’s extensive and detailed allegations covering a broad range of conduct…. Certain allegations — such as those involving Trump’s discussions with the Acting Attorney General — are readily categorized in light of the nature of the President’s official relationship to the office held by that individual. Other allegations — such as those involving Trump’s interactions with the Vice President, state officials, and certain private parties, and his comments to the general public — present more difficult questions. Although we identify several considerations pertinent to classifying those allegations and determining whether they are subject to immunity, that analysis ultimately is best left to the lower courts to perform.” The Court added that “it is incumbent upon the Court to be mindful that it is ‘a court of final review and not first view’” (noting that the Court had no prior precedent to rely on, that the case raised unique and significant Constitutional questions, and that the legal proceedings had been expedited in both the lower courts and the Supreme Court resulting in a dearth of legal fact-finding and briefings).

What does this line-drawing mean with respect to charges filed against a President? For example, because a President has “exclusive authority” over the investigative and prosecutorial functions of the Justice Department and its officials, he is “absolutely immune” from prosecution for any alleged conduct involving discussions with Justice Department officials. The Court in Trump v. U.S. confirmed that “investigation and prosecution of crimes is a quintessentially executive function.” Therefore, the allegation in the Justice Department’s indictment that “Trump and his co-conspirators attempted to use the Justice Department ‘to conduct sham election crime investigations and to send a letter to the targeted states that falsely claimed that the Justice Department had identified significant concerns that may have impacted the election outcome’” must be dismissed. “Trump is therefore absolutely immune from prosecution for the alleged conduct involving his discussions with Justice Department officials.”

The Court further held that the other criminal allegations against President Trump require more factually difficult determinations. For example, the indictment alleged that President Trump “attempted to enlist the Vice President to use his ceremonial role at the January 6 certification proceeding to fraudulently alter the election results.” The Court stated that “[w]henever the President and Vice President discuss their official responsibilities, they engage in official conduct. Presiding over the January 6 certification proceeding at which Members of Congress count the electoral votes is a constitutional and statutory duty of the Vice President. The indictment’s allegations that Trump attempted to pressure the Vice President to take particular acts in connection with his role at the certification proceeding thus involve official conduct, and Trump is at least presumptively immune from prosecution for such conduct. The question then becomes whether that presumption of immunity is rebutted under the circumstances…. We therefore remand to the District Court to assess in the first instance … whether a prosecution involving Trump’s alleged attempts to influence the Vice President’s oversight of the certification proceeding in his capacity as President of the Senate would pose any dangers of intrusion on the authority and functions of the Executive Branch.” Although these and other allegations of Presidential wrongdoing would have been factually analyzed by the District Court on remand, that process was terminated upon upon President Trump’s re-election. However, what the Court’s holding means is that actions of a President that include those raised in Trump v. U.S. may be criminally prosecuted and require close legal and factual analysis. That means that no President receives a “legal pass” with respect to such actions.

That conclusion is reinforced by the Court’s additional holding that “There is no immunity for unofficial acts.” Such alleged “unofficial acts” included President Trump’s interactions with persons outside the Executive Branch in attempting to convince certain State officials that election fraud had tainted the popular vote count in their States. The Court remanded to the District Court the determination of whether President Trump’s conduct in these regards qualified as “official” or “unofficial.”

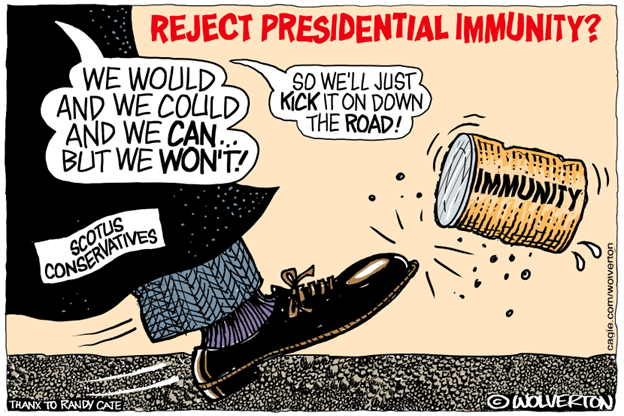

The decision has been criticized as undermining “critical checks on executive power” and is “an affront to democracy and the rule of law.” It also has been critiqued as being unnecessarily broad. Either or both may be valid. However, the point is that the ultimate legal determinations have been kicked down the road. The Supreme Court most certainly has not exonerated Presidents from criminal actions. Moreover, the Supreme Court’s decision does not prevent the State of Georgia from proceeding with its racketeering case in State of Georgia v. Donald J. Trump. It also doesn’t prevent Congress or the courts from criminally challenging the President should foreign officials use economic incentives to influence the President (for example, with respect to the Trump meme coin $Trump under Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution (which prohibits government officials from accepting “emoluments” from foreign States)) — after all, well-targeted “emoluments,” as well as consistent ones, are bribes. The book on Presidential Immunity therefore remains a work in progress.

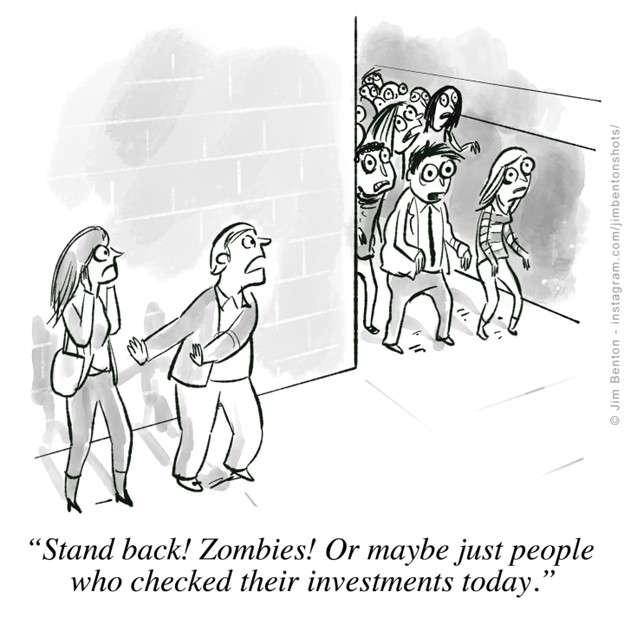

Finally (from a good friend)

No Comments