06 Sep Stagflation

“Stagflation is not a four-letter word.” – The Lonely Realist

“Stagflation” is not necessarily a bad thing. It can be benign. It denotes a combination of slower-than looked-for GDP growth coupled with a higher-than-desired level of inflation. Given that most alternatives to stagflation are worse – the only good alternative being increasing growth and low inflation –, mild stagflation can be a good outcome for economies going through turbulent times…, as America currently is. Economists who are predicting stagflation today see only a modest version in America’s future. As a consequence, the risk of stagflation ought not to be viewed negatively and should not be equated with the highly fraught version that persisted during the 1970s.

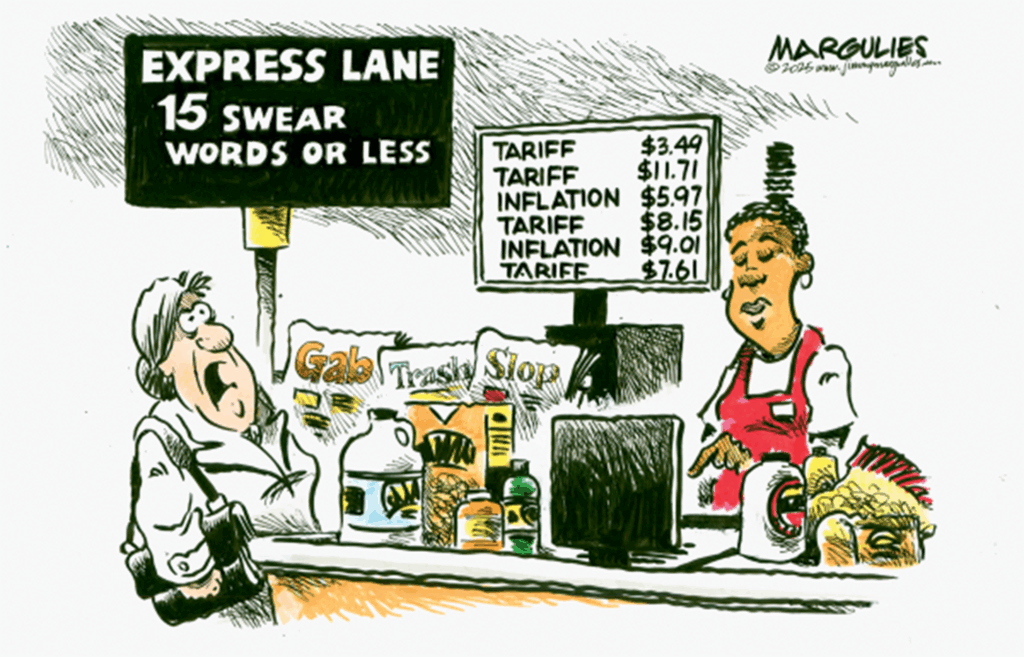

The U.S. today is experiencing slowing economic growth – but growth nonetheless – and a higher-than-desired rate of inflation – that is, mild inflation. The former is apparent in America’s depressed housing market (where housing typically leads economic growth), softening employment numbers (recently decried by President Trump as invalid – and he accordingly “shot the messenger” so that Americans are likely hereafter to receive less downbeat numbers), weakening labor demand (evidenced by declines in non-farm payrolls, the JOLTS survey of job departures, government employee “departures,” etc.), a crackdown on immigrant workers, a reduction in the issuance of work/student/visitor visas, and a massive binge of AI data center over-spending (which has been the primary motor of GDP growth over the last three quarters – meaning that absent such over-spending, U.S. growth would have dropped dramatically (perhaps to as low as 1%)). Inflation is in virtually every economic forecast based on the projected impact of Trump Tariffs (the average tariff rate in the U.S. today is 18.2%, the highest since the Smoot-Hawley tariffs of the 1930s), Trump 2.0 pressure on the Fed to cut interest rates (thereby devaluing the Dollar), wholesale price increases (which surged 0.9% in July over June and 3.3% year-over-year), the potential for escalating trade warfare, and ballooning Federal deficits and debt (which have led to weakening bond prices). Despite economic stagnancy and inflation woes, economic growth at any level is a good thing (and America’s growth continues to lead the world). Moreover, modest inflation can have a salutary effect on debt and deficits, also a good thing. The alternatives are worse. Ray Dalio is among those who have been predicting a debt-induced crash that will occur within the next few years. A slowly growing U.S. economy with moderate inflation is a far better outcome and, in contrast to more rapidly rising debt and deficits, one less likely to result in an economic blow-off.

The term “stagflation” was coined in the 1970s in response to the severe economic pressure brought to bear on the U.S. economy by oil price shocks. The consequence 50 years ago was that the U.S. economy was forced into a sudden downshift that resulted in slowing economic growth coupled with increasing inflation and unemployment. Addressing the impact required harsh economic measures. Those measures were finally administrated at the end of the decade by Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker, raising interest rates to >19%. Out-of-control stagflation called for severe corrective action. That is far from the situation today.

The fear of stagflation in 2025 has nothing to do with external forces such as those that buffeted America in the 1970s. Today’s stagflationary wounds are self-inflicted and stem from ballooning federal deficits and debt, direct Federal government interventions in the economy, the threatened impact of Trump Tariffs, and a stubbornly higher-than-wished-for rate of inflation. Although the Fed had expected the rate of inflation by now to have shrunk to a targeted 2%/annum, inflation instead has bounced up from its recent low of 2.4%. The New York Fed’s August survey of consumers’ inflation expectations for the next year shows an increase to 3.1% and the Fed now expects 3.1% core personal consumption expenditure inflation (PCE). Despite these projections of increasing inflation, the market expects the Fed to reduce interest rates later this month and do so again over the coming year in order to support housing and offset slowing growth caused by tariffs, slowing labor supply growth, and the gulf between AI spending and the availability of power to supply AI needs. Lower interest rates would be expansionary, arguably a good thing, and inflationary, not so good.

It is not surprising that stagflation seductively beckons. Slowing growth, after all, is still growth, and inflation slightly above 3% can be a benefit by reducing the cost of repaying America’s unpayable $37.3 trillion debt. In addition, the lower interest rates favored by Trump 2.0 would reduce the relative value of the Dollar and thereby incentivize exports (but also would increase inflationary pressures). It also would bring down annual interest costs that are an increasing percentage of America’s deficits. Stagflation accordingly could well be an economic preference, surely over its more fearsome cousins, recession, debt crisis, and worse…, each of which would require a catalyst to unbalance the current stagflationary status quo (although the risks of a debt crisis will still need to be addressed by Congress and the President). Although maintaining stagflationary stability will be challenging, in the absence of a materially hostile change in the global economy or an adverse geopolitical, health or “black swan” event, the expectation is that the U.S. economy will continue on a moderate and arguably benign stagflationary course.

However, although there currently is no economic indicator that points to a crisis, there are imminent apparent risks to economic stability, including the September 30th budget deadline for averting a government shutdown. There have been 14 such shutdowns since 1981, most of which were short-lived, the most recent being during Trump 1.0 that, however, lasted 34 days. The September 30th deadline should be of concern, especially since President Trump has made clear his lack of fear about government shutdowns, seeing them as politically useful in giving him the power to make cuts at Federal agencies. The month of September, often seen as a perilous economic month for other reasons, therefore may be all the more perilous this year.

Finally (from a good friend)

No Comments