18 Oct Weapons of Mass Value Destruction

“ETFs and rare earths (and even soyabeans) are economic weapons.” – The Lonely Realist

An ETF is a public investment fund that trades on stock exchanges in the same way as a single stock (and with more liquidity than a mutual fund). An exchange traded fund (ETF) in equities differs from an investment in a single stock because it represents an investment in multiple (often sector-related) companies, offering a simple and affordable way for individual investors to diversify among a variety of individual stocks (often with the option to do so on a leveraged basis). ETFs are potent vehicles for risk reduction through diversification. How, then, could they become weapons of economic destruction? Easy: In the event of a loss of confidence – an “economic fire” –, ETFs would be the consummate accelerant.

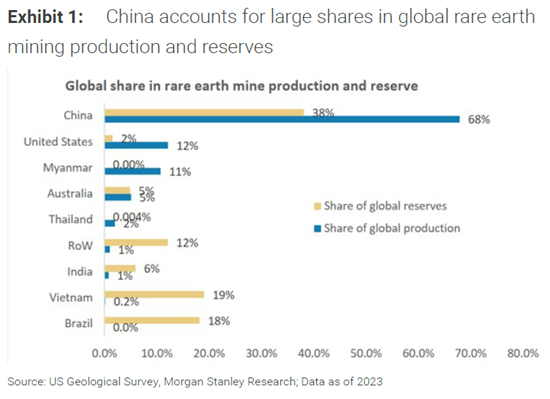

Rare earth elements (REEs) are 17 metallic elements that are an essential part of more than 200 products, including high-tech consumer products that use semiconductors, such as cellular phones, computer hard drives, vehicles, and flatscreen monitors and televisions. Significant defense applications include electronic displays, guidance systems, lasers, and radar and sonar systems. REEs therefore are important economic building blocks. An abrupt shortage could devastate industry (as well as specific industries) and thereby ignite an “economic fire.”

But soyabeans? They’re simply an agricultural commodity. And yet, the U.S. soyabean industry is significant, having an estimated total economic impact on the U.S. economy of $124 billion representing ~0.6% of GDP. The fact is that soyabeans are America’s number one agricultural export, supporting over 500,000 jobs. Because their production and export are impactful, they are economically weaponizable, making America’s soyabeans a “flammable commodity.”

The U.S. economy is not self-contained…, or self-sustaining. It is exposed to a broad range of external sparks inputs, including from suppliers and foreign consumers, as well as being subject to unforeseeable events – so-called black swan risks (including, perhaps, from stablecoins and/or private credit). America’s highly diversified, consumer-driven economy has led many to believe that America is immune from externally-generated risks and that America, moreover, has learned the lessons of 1929, 2000 and 2008 by incorporating comprehensive protections into its economic and legal systems. Unfortunately, that is not the reality. Although the geneses of prior economic crashes may (or may not) have been adequately addressed, today’s times differ from past economic environments. Among other things, the U.S. is sitting on an unprecedented ~$38 trillion of Federal debt and $2 trillion of annual deficits. It is part of a geopolitically tumultuous world in which its internal conflicts have significantly increased its vulnerabilities. COVID-created and tariff-disrupted supply chains are in disarray at the same time as equity and debt markets are at breathtaking heights…, and could be toppled by a loss of faith in a beloved industry…, like AI. Moreover, we are in the midst of an air-pocket of de-dollarization that could have an accelerating impact on the U.S…, as well as on the global economy.

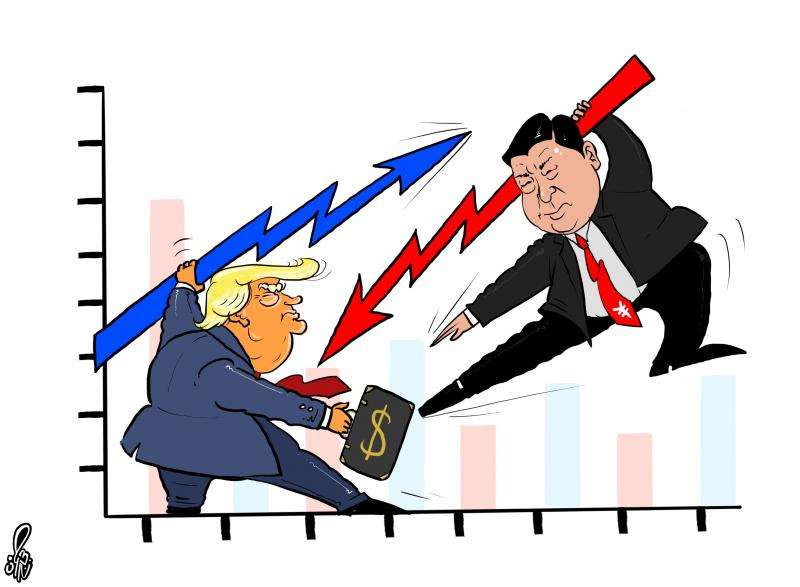

The escalation in America’s ongoing trade war with China has seen both sides threatening and, most recently, with China deploying increasingly potent economic weapons. American threats of significantly higher tariffs led China to respond with a home-grown array of countermeasures, the most prominent of which are restrictions on the export of REEs[1] (as well as of intellectual property related to REE refining) and elimination of American soyabean purchases in favor of Brazilian imports. China also has imposed tariffs on other strategic American agricultural goods, is charging port fees, and has threatened tariffs equal to threatened American tariffs (including on key American exports such as coal and liquefied natural gas). In short, the U.S.-China trade conflict has evolved into a complex set of thrusts and counterthrusts that extend far beyond traditional tariffs into non-tariff barriers and strategic export controls. “Sparks” are flying. Where might they land…, and what might they ignite?

Market sensitive ETFs are a possible landing area…, and a potentially consequential one.

If for some reason investors began to exit one or more strategic ETFs, those ETFs would have to sell some of their underlying equities, which would place downward pressure on the prices of those underlying equities and create a self-reinforcing cycle where individual equity sales trigger necessary ETF sales that trigger further individual equity sales…, etc. The momentum buying that fueled upward spiraling stock market values would reverse into waterfall selling. Passive ETF products that propelled stock prices upward in lockstep, creating markets that became divorced many believe have become divorced from fundamental value, would reverse. At a certain unknowable level, the markets would top-out. The popularity of ETFs nevertheless is understandable. They are a cheap and easy way to access exposure to almost any sector in any asset class. Concomitantly, the size and scale of the industry has grown, roughly doubling every four years, with total global ETF AUM hitting $13 trillion in 2024, roughly equivalent to ~9% of AUM in the global investment management industry. The scale is relevant because ETFs are designed to be a liquid asset, traded frequently in the secondary market. It is worthwhile to note that the U.S. ETF market today has ~$2.7 trillion in assets and as of late 2024, equity ETFs held $10.3 trillion or 26% of the total net assets in U.S. investment funds.

The linkages between disparate AI-related assets that today are central to America’s economy have created a critical weakness. The fates of OpenAI, Anthropic, Microsoft, Alphabet, Nvidia, Oracle, Tether and Coinbase are closely intertwined. Weakness in one or more could become contagious, doing so through ETFs (or otherwise) as well as through increased crossholdings. All are affected by China’s REE policies.

When might a liquidity mismatch inherent in an ETF become an illiquidity accelerant? One way would be in a panic such as occurred following Liberation Day. The Liberation Day panic quickly subsided. There weren’t any ripple effects. The market shrugged off concerns. History indicates, however, that there will be panicky times in the future. At some point, they will not subside.

Finally (from a good friend)

———————

[1] Note that China controls both the extraction and production of REEs:

No Comments